Town of Pidhajtsi in the State of Ternopil in the heart of western Ukraine, or historical Halychyna

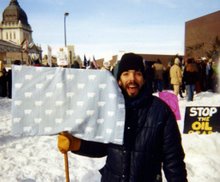

Last March, 2005, I returned from 8 months in Ukraine, where I spent most of my time in Pidhajtsi, a small town of about 7,000 people that is 70 km from the city of Ternopil in the state of Ternopil (states or administrative regions in Ukraine are named for their capital cities). I lived with relatives and learned to do things like bring in the fall harvest, speak better Ukrainian, and drink such amounts of horylka (Ukrainian for vodka) that I never would have imagined humanly possible, had I never gone to Ukraine. This was my first visit to my ancestral homeland, and I fell in love with it, in part because of the conditions in the country; but more on that later. I did quite a bit of wandering, and spent significant chunks of time in Lviv, Ternopil, Ivano-Frankivsk, some villages near Kosiv and Kolomija in the Carpathians, Zhytomyr, Poltava, and of course, Kyiv. In the mountains, I got to dance a real, traditional arkan at a Hutsul wedding (what you see big Ukrainian dance ensembles doing only vaguely resemble the real thing). And of course, I experienced the build up to the elections and the Orange Revolution (OR) itself. I was both an active participant in and witness to the events of the OR, not just in Kyiv but in various parts of the country. I feel that it is extremely important to emphasize to people who were not in Ukraine at the time that the OR did not happen in Kyiv alone, that there were demonstrations in cities, towns, and even villages all over the country. Thus in the course of those fateful 3 weeks, I wandered from city to town to village in many parts of Ukraine, taking photos and video, and wrote reports on what I saw and heard happening to a list-serve I established, as frequently as was possible.

This was all before I learned how easy it is to start one’s own blog. I have been writing a list-serve about my thoughts about and experiences in Ukraine in particular, and about conditions in post-communist “Eurasia” in general since June 26, 2004, my first day in Ukraine. This blog is a continuation of that list-serve project. You will be able to find here (eventually) everything that I wrote during my months in Ukraine, as well as new stuff. The Orange Revolution stuff is very interesting, but I encourage you to at least read what has turned out to be the most popular piece I wrote--a descriptive, pretty much ethnographic essay in which I tried to convey something about life in the town of Pidhajtsi.

As for what one can expect to see in the future on this blog, general themes I like to write about include:

Why did the OR happen? What was it all about it?

Stories about everyday life and travel in Ukraine. As for "travel," I am fascinated by the very different conceptions of both space and time that provincial or rural Ukrainians have compared to those of a (post)modern Westerner.

Stories from people about their experiences with corruption--how did the corruption of the government have a demoralization effect on the population at large in Ukraine? I will recount personal stories about local officials selling off machinery to enrich themselves, etc.

Ukraine's political structure and the ongoing issue of political reform.

The political or public personalities of leading politicians. Who is Yushchenko? Tymoshenko? Poroshenko? Etc.

The grassroots-history of PORA! and other organizations, such as Chysta Ukrajina, etc.

Role of the US in the OR. I am very critical of what I perceive to be a gross overestimation of the role played by the US in the course of the OR by people on both the left and right of the political spectrum in the West. The people of Ukraine made this revolution happen, not US NGOs nor the CIA, even if Ukrainians were assisted from abroad. On the other hand, I am also very interested in crtitiques of neocon policies of low-intensity agitation for regime change.

Comparisons between the OR and other pro-democracy movements and rebellions taking place in the world today.

Comparisons between life in Ukraine and in the US and EU (one of my favorite topics).

Critically investigate what the WTO, “market-status,” the EU, IMF/World Bank, "market-economy" and "European standards" and "European-readiness" mean in general and for Ukraine in particular.

The question of what kind of Ukraine contemporary Ukrainians imagine their country to be, and what they want it to become after the OR. I spent my last few weeks in Ukraine interviewing Ukrainians about precisely this theme, and keep talking to people about this via email. Is Ukraine a pluralistic, and multicultural and multilingual society, and should it be? Or is it a place just for Ukrainians that has suffered a tragic history of cultural genocide that needs to be reversed at all cost? And do Ukrainians want capitalism with an American face, or capitalism with a more European one?

This is not a complete list of themes, and stylistically the pieces posted here will sometimes be narrative accounts of daily life, sometimes newspaper articles (I have and continue to publish pieces about Ukraine, mostly in diaspora papers), sometimes rants, and often just thought-pieces. Very little of what will appear here will be “professional” or academic, with citations, etc. But I am working on a number of such essays as well, which will appear here eventually. And one other note: I do my best with grammar and spelling, but I won't always be thoroughly editing my posts.

I should make it clear that I write from a liberal—neh, left—point of view when it comes to issues of Ukraine’s integration into the global economy. I want Yushchenko and his administration to fight hard for high wage protections, environmental protections, high-quality universal healthcare and higher education, etc.; in short, to fight against World Bank/IMF “restructuring” programs and demands for "austerity measures," as they steer Ukraine into the world economy. I want to see the government of Ukraine join forces with the anti-Neo-Liberalism rebellion taking shape in the world today, as people and governments throughout the global south (and hopefully now the East) get organized to demand more equitable trade agreements with the West and North (and I think many Ukrainians will want their government to do so, too, as average Ukrainians become increasingly familiar with the globalized world order into which their country is becoming more integrated). In short, my thoughts are guided by the motto increasingly heard in the global south, which is one that I think Ukrainians will be quick to adopt, too, as their country becomes more integrated in the global economy: “Just any job is not always better than no job at all!” This is especially the case in countries, like Ukraine, where a large portion of the population can get by as subsistence farmers with occasional, part-time wage labor. The point is that people in Ukraine and many countries of the global East and South want the political conditions and standard of living in their countries to actually improve. They don't want just to replace a local oligarchy and low-income slavery to either the land or some job with few health-benefits, few opportunities for higher education, and an economy with total disregard to environmental conditions with a foreign oligarchy that will basically maintain their low-income slavery either to the land or some job, again with few health-benefits, few opportunities for higher education, and total disregard for environmental conditions. They want good-paying and not any just any job, universal healthcare and education, and a healthier, cleaner environment to work and live in: these were the leading principles and promises of Yushchenko's campaign, in addition to his promise to clean-up corruption. They also are what most Ukrainians I talked to more or less thought they were fighting for. To my mind, and to many once again in Ukraine, only a viable social democracy can guarantee such things, not the American system--a social democracy on the European Union model, or on the model being worked out in certain Latin American countries. But activists around the world know how much the IMF and World Bank are fans of such systems.

One more concluding remark: The countries of Eurasia, of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, are going to play an increasingly significant role in global geopolitics. These are nations with high unemployment rates and vast resources that are barely integrated into the global market economy. Standing in the way of their more complete integration is the fact that these are (or in the case of some, have been) nations with semi-authoritarian governments rife with corruption and oligarchs who have robbed Western investors and aid agencies left and right. Once these regimes are replaced, and the oligarchies and much of that corruption is curtailed, new boulevards will be thrown open for the legions and cannonballs of neoliberalism. Such regime change is eagerly anticipated by many in the West, especially in but not limited to neoconservative circles in the United States (see Zbigniew Brzezinski’s The Grand Chessboard that was widely read in Washington, D.C. policy circles, for an indication of the centrality of Eurasia to the future of American and global geopolitics). Regime change is also eagerly awaited by the popular masses of Eurasia, but most of them want social democracy and fair trade, not neoliberalism and free-trade, according to my own research in Ukraine and a political hunch that is derived from the notion already mentioned that for most, not any job is better than no job in a country in which it is still possible to survive as a subsistence farmer and part-time wage laborer.

However, this is a part of the world about which most people in the West are, in general, quite ignorant, especially when it comes to grassroots sentiment. This means that Westerners have difficulty navigating the web of roles being spun by people’s movements, NGOs and foreign powers in what looks promising like it will become a new Springtime of Nations. But even worse, many people in the West only know stereotypes when they do think at all about the region, which includes even educated Westerners, and even politically active ones to boot. Far too many in the West traffic in such stereotypical notions about Eastern Europeans and Central Asians as, "Aren't they all just rabidly anti-Semitic in Eastern Europe?" or "Aren't they all, more or less, nationalist zealots? or "Isn't everyone, even everyday people, just basically corrupt in Eastern Europe or Central Asia?" or "Isn't it dark and depressing there?" or "Isn't it true that they don't even know what a microwave is?" or "Weren't all the anti-Soviet Popular Fronts just CIA fronts?" etc. People also make a fetish and noble savage out of one figure of Eurasian life, the Gypsy, which has come to resemble little of its true self in the Western mind. But don't get me wrong--Romani culture fascinates me and I have had long arguments with certain people in Ukraine, waging war against their negative stereotypes about Gypsies (which are basically the same as American stereotypes about "Blacks"). In general, my experience in Ukraine taught me that there is much, much more to Eastern Europe and the East Slav world—and by extension and more “political hunches” Central Asia—than what the Western image even hints at. In short, the Western image of this fantastic region of the world resembles little of what the life and culture there really is like.

Of course, the average person in the West can not be blamed for this. Education and information in the West about this region is minimal and often distorted, even though more than hald of Europe was encompassed by the Cold-War definition of Eastern Europe. To focus on Eastern Europe alone (for Central Asia and Eastern Europe are sensibly thought of in unison as "Eurasia" only because they share a common Soviet past and today share a similar post-Soviet struggle), another striking statistic is that there are 256 million speakers of Slavic tongues, making Slavic the largest language family in Europe; and there are about 20 million people with Slavic roots in the US. I don't mean to focus only on the Slavic population of Eastern Europe and North America, however; one should note that the various peoples of and events in Eastern Europe have played a fundamental role in European history as a whole, and this means that European history courses should also focus on the history of Eastern Europe. However, what one usually learns from standard European history textbooks are only those portions of Eastern European history that matter to the telling of the story of Western Europe. What is more, there is a strong Russocentric bias among Western scholars and thinkers and policy-makers when it comes to thinking about the history of and contemporary situation in Eastern Europe, and this leads to all kinds of distortions in the popular mind as well (such as, "Isn't Kyiv a city in Russia?").

However, I will single out the activist community in the West for criticism, only because one should expect political activists to be better informed. Unfortunately, the political activist community in the West traditionally has barely paid any attention to issues and events in Central Asia and Eastern Europe, and have thus left it up to the mainstream media, or to pundits of both the right and the left who know nothing to little about the region, or who only know the Russocentric interpretation of events, to construct the representation of Events there; and the activist community has the tendency of picking up these representations as their own. Also plaguing the activist community is deep skepticism about the authenticity of people's movements in Eurasia--"I mean, come on," people say, "what the popular masses or the multitude of Eurasian countries are clamoring for is, in part, well, more capitalism, isn't it? And they did reject a worker’s state, didn't they?" The answers to these questions are anything but simple or obvious.

Thus, perhaps more so than anything, this blog is an effort to make a difference by presenting pieces that cut through this wall of ignorance, and is an effort to convey something REAL, rather than ideological and/or imaginary, about the fantastic land called Ukraine, and of the Eurasia of which it is part, whether one wants it to be or not. But don't get me wrong: I do think Ukraine is an European nation (this is not a contradiction), and I am a big supporter of Ukraine’s bid to join the EU; however, my support is highly qualified, which is something that will have to be explained in some future post. . .

Thus, in short the two major themes of this blog are:

1) Daily life in Ukraine as I experienced it.

2) Ukraine and Globalization (in which catergory I include the OR).

I hope that you will enjoy this site.

Us’oho najkrashchoho (All the Best),

Stefan Iwaskewycz