On the morning of November 22, I woke up early unable to stay asleep, as I was eager to listen for news about the previous day’s runoff election. Both my 23-year-old second cousin and I had been up quite late, listening to reports on Radio Era of widespread violations, of exit polls giving Yushchenko victory, and of the bizarre arithmetic of the Central Electoral Commission pointing towards a Yanukovych victory. Radio Era was more reliable than any of the major Ukrainian TV networks, and we didn’t have the satellite dish that one needs to get Channel 5. As I returned to my spot beside the radio, I found Oksana already there, sitting on the edge of her seat, listening pensively. The news was bad: It was indisputably clear that Ukrainian authorities had behaved the previous day even more shamelessly than they had on October 31.

It was Monday. I was in Pidhajtsi (pop. 7,000), a town in Ternopil oblast. The internet at the computer club in Pidhajtsi was down that day—as it frequently was—so I decided to head for the neighboring, larger town of Berezhany (pop. 25,000). I needed to get on the net and see what was happening elsewhere in the country, and to write emails home. As we boarded the bus that afternoon—my cousin came with me—we knew that the multitude gathered on Independence Square in Kyiv was already 200,000 and growing.

In Berezhany, we not only found an internet club, but a revolution starting. Walking to the center of town from the bus station, we saw something incredible. A car was driving around from which the passenger in the front seat was shouting through a megaphone, "Esteemed Berezhantsi, your country is being stolen from you! Do not take this lying down! Rise up, Ukraine! Come to the meeting at 3 PM on the Central Square!”

I had goose bumps all over. I turned to my cousin and said, "Maybe it really is starting." She said, “I hope so.” The night before, as she went to bed, she had said, "Something has to happen tomorrow." Oksana is now a schoolteacher in Pidhajtsi, where she was born and raised.

In the center of town, 1,000 people were assembling in front of the local offices of one of the political parties that are part of the Our Ukraine bloc. A television was set up outside, turned to the opposition Channel 5, which was re-broadcasting the speech Yushchenko made earlier that day in Kyiv, telling people: It’s time to fight! Come to the maidan! Demonstrate! It was the first time that I heard this speech that should go down as one of the most important moments of contemporary Ukrainian history, as the statement that began a revolution whose aim continues to be, putting an end to Ukraine’s post-Soviet era. By evening, reports were of 350,000 or more in Kyiv, and of a tent camp already established.

After the speech finished airing, speakers addressed the crowd in Berezhany. Then a call was made to march to the county administration buildings, where people wanted to demand an explanation from local officials of their role in the falsified vote.

We arrived at the county administration building shouting "Shame! Shame!" By now, the multitude had grown to at least 4,000. Person after person spoke of various reports of violations from around the country. Someone mentioned that observers from Berezhany had not been allowed to leave their hotel by the local police somewhere in eastern Ukraine. One man raged, "Did they [authorities] think that they didn't even have to try and hide their deeds? Fellow Ukrainians, maybe we have been asleep for too long. Today, we must say ‘Enough!’ Shame! Shame!" and the multitude joined in shouting that word. Their voices were angry, fierce. This was no joke, no game, what was happening here—a future of either slipping further back into an even more Soviet-like past, or one with a healthier and more equitable economy and more democracy, was being decided.

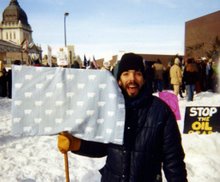

I zipped to and fro, taking photos and video. Many people looked directly into my camera lens and smiled; some held up a fist or what in Ukraine is a victory, not peace, sign. I noticed some 10- year-old boys holding eggs in their hands. They were standing near the entrance to the building, and were waiting for the head of the county administration to come out! Some people in the building opened windows and waved to the multitude, which responded with a large roar of approval. After more speeches, the call came out: Everyone! Return tomorrow morning by 7:30 AM and continue the blockade! We then sang the national anthem, and headed home. While singing, I noticed an old man who had tears streaming down his cheeks. This same fellow earlier had said to me, “Finally, you young people are doing something for our country, like we did when I was young. I am proud today.” He had been a partisan, a member of the OUN.

The Orange Revolution thus began in Berezhany, where the picket of county buildings continued for weeks. Similar things happened in towns and villages of all sizes. Kyiv was not the only place that the Orange Revolution occurred, nor was it the only place in which people took serious risks of personal safety when they chose to picket and demonstrate. The fate of the country was determined by millions of people at pickets and demos throughout Ukraine.

Before catching the last bus back to Pidhajtsi that evening—which had also had a demonstration of 1,000 people that day, and which also had ongoing demos for three weeks—we headed off to the computer club at the university. As I sat writing a report home (which can read here via the OR links), I listened to people talking. Plans were being made to head to Kyiv. One guy said that a good friend of his, who had spent two years picking oranges in Portugal, had left him a message saying, “I am now in Kyiv. You have to come. Kyiv is harvesting oranges today.”

See the photos below from Berezhany. As soon as I figure out how to do it, I will be including photos interspersed with text instead of as a seperate post!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment