Mykhajlo wears what must count as the thickest glasses ever worn by a human being--they should definitely find a place in a Museum of Strange and Unusual Medical Devices, such as we have here in Minneapolis. He told me that his eyes are slowly "melting." He said that he feels like his internal organs are slowly decaying, changing form, and becoming something like a moosh of organic flesh without distinctions. He is becoming a body without organs (but not in the liberating sort of way that certain poststructuralists have celebrated). He says that at some point his body will prematurely just stop working and become a body without organs and without a soul, without a life. It could be soon, or it could be in a while.

Mykhajlo says that he spent weeks driving materials out of the Chornobyl site on a flatbed truck. He gets a medical pension, which he receives though no doctor has ever told him for sure what his problem really is. He complains that the pension, of course, is meager and that in the early 1990s, it wasn't even paid.

He did not become sick right away, he says. It wasn't until years after the disaster that he started to feel ill. He says the effects have started to accelerate. He is a 40 something man who walks with a cane. He is tired all the time. He is a warm enough fellow, quite willing if not quite eager to talk about the issue. Though I have not spent much time talking with him--he is yet another of my father's cousins from the village of Sil'tse not far from the town of Pidhajtsi--he has never asked me for money, just for my understanding. Do I understand how many others like him there must be in Ukraine? He hoped that Yushchenko would make a difference in his situation. I wonder what Mykhajlo thinks now (I don't mean that as a cheapshot at Yushchenko, but rather, I really do wonder what he thinks now. . .).

He is angry about what happened to him, but not in an unhealthy kind of way, or, that is how it seemed to me. He has a very justifiable anger, but he doesn't hold it in that way that easts away at a person from the inside out, making worse an already-bad condition.

He says that they--the drivers--were told at the time that their job wasn't dangerous. They weren't hauling (radioactive) materials from the immediate site of the plant, afterall, but from one area to another within vicinity of the plant.

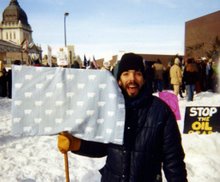

This is written for him, and for the many invisible victims of that disaster.

I hope I will be able to spend more time talking with him next time in Sil'tse.

***********

UPDATE: Some Chornobyl articles:RFE piece on other victims whose stories are similar to Mykhajlo's here.

RFE piece on reactions to a recent UN (IAEA) report on Chornobyl here.

About the Greenpeace report that claims that the UN (IAEA) report grossly underestimates the number of those effected here.

Ukraineblogger "Leopolis" has posted a bunch of interesting documents and pieces dealing with the disaster here.

2 comments:

Dear Dykun,

Thank you for a very interesting and humane piece on a "victim of Chernobyl". It is only by such accounts that one may put this disaster - as well as so many other during soviet times - in true perspective.

Yours,

Vilhelm

Thank you for the comment. Perspective is what is needed these days it seems. . .The UN report was such a disappointment for people like Mykhajlo who need international groups to back up their claims to suffering with strong statistic and rhetoric as they struggle for more assistance and attention and better care. . .

Post a Comment