Spirit and the Struggle:T

Spirit and the Struggle:The most basic principle of materialist philosophy in all its variants is the notion that things do not happen in the world because of spirit. History and events do not take place as part of a process of spirit realizing itself; it is through things

happening that some thing we might call "spirit" is constituted and that some process we might call "progress" happens (though there always also is regression). Since Marx stood Hegel on his head, progressives have been aware of this: the world is constituted in

praxis, i.e., struggle. "Before Being, there is politics" (cf.

deleuze/guattari). It is through struggles (becomings) of all sorts that our Being-in-the-world is produced and

reproduced. The human world is produced in the multitude of class or economic struggles, political struggles, cultural struggles, reproductive struggles (the struggle for liberal reproductive rights, or control over one's own body, especially by women), sexuality struggles, academic and intellectual struggles, etc.

T

The key word in all of this is not spirit, but struggle. Better than the birth of spirit, the Orange Revolution is thought of as a significant moment in Ukrainians' post-Soviet struggle to change their country, a struggle that is far from accomplished and that still requires grassroots action and organization--which was, at the time of the Orange Revolution, still only at a rudimentary level, appearances to the contrary aside.

(An active NGO sector is neither a replacement for nor a necessary indication of a nation-wide, consolidated and deeply-rooted grassroots movement for change.) The Orange Revolution was still just a beginning, not a culmination. Yushchenko's inauguration day proclamation of the end of Ukraine' s post-Soviet history was premature (unless the nature of elections and relative freedom of press are the sole issues defining the boundary between post-Soviet and post-post-Soviet), and what is more, was an indication of the degree to which Yushchenko and gang considered the need for real struggle already over. This in turn indicated that Yushchenko and gang

would soon capitulate to Ukraine's oligarchic or elite-driven political system and capitalism instead of leading a genuine, progressive struggle against oligrachic control. (Their capitulation to their oligarchic adversaries and betrayal of their Orange Revolution promises is an event that is marked on the pages of the ill-considered, so-called "Memorandum of Understanding," signed by Yushchenko and Yanukovych in the autumn of 2005.)

Like Kuchma and gang, though not to the same degree, Yushchenko and gang in the last two years have pursued a high level of compromise with their oligarchic adversaries (it was right to point out that many in Yushchenko's gang are oligarchs--business tycoons with political clout--and to claim that the Orange Revolution was in part the opportunistic rebellion of certain millionaires

against Ukraine's billionaires and their cronies), instead of using the full strength of the will they had backing them after the Orange Revolution. In so doing, and though they promised to struggle for deKuchmization, they have betrayed those who really made the Orange Revolution happen, and are complicit in the (re-) creation of a Kuchma-lite system that is now taking hold in Ukraine, one in which only some (perhaps none!) of the extremes of Kuchmism

are eliminated. They have shown that they are preoccupied with inter-elite struggles for their own sake and that they are nearly as removed from everyday people as are those they once called bandits and criminals. As Kuzio put it (

here), Yushchenko has failed, as much as his predecessors, to be a listening president. In Yushchenko's case--in an effort to bring about the important

disenchantment of the Yushchenko myth so widely spun in the heady OR days--it is important to recognize that one does not become a politician of the multitude of Ukrainians simply by virtue of having roots in a village one left behind long ago and by having a (bourgeois) passion for (collecting) folk art and (the leisurely study and promotion of) Ukrainian history. Yushchenko was only but ever a reluctant revolutionary (

here),

and has with almost total consistency refused any warrior path. The Orange Revolution was a remarkable exception in his technocrat's life. He prefers what he frequently called "clean politics," or to be what he fancies a proper, European gentleman-politician, indeed, an elite--real struggle is too messy, especially for the investors and governments

abroad and for the interests of captial at home whose desires the president sought to fulfill more than those of the people whose struggle he claimed to champion. In this context, the manner in which the president chose to mark the second anniversary of the Orange Revolution, with an elite gathering far removed from "the maidan" and its people, is no surprise (

here).

And so the necessity of (an anti-oligarchy, anti-Kuchmism) struggle remains.

S

Spirit can always be lost. If the world is not the product of a spirit that is inevitably heading toward a telos (goal)--i.e., Freedom--but is created as the result of a wide variety of everyday becomings or struggles, then gains can be lost. "Freedom" is potentially gained (and lost) in struggle. If one doesn't like Marxist talk, perhaps one can appreciate terms borrowed from Zen Buddism: The Buddha was never content to relax. The Buddha had to renew his efforts everyday, lest he fall from his Enlightenment.

If the Buddha can slip from Enlightenment without daily struggle and effort, Ukraine can loose the spirit of the Orange Revolution that hasn't yet been fully realized. Like any person after a flash of realization, Ukraine as a nation can become stuck in a semi-realized state and can succumb to old and new illusions, despite the Orange Revolution.

The Orange Revolution was a collective

kensho, a momentary glimpse of Enlightenment, or a glimpse of the Enlightened world Ukrainians could live in and build. Realizing it will take ongoing effort, or struggle.

T

This is not to say that there is no positive or progressive accumulation of successes from previous struggles--that is, gains of the oppressed vis-a-vis the powers-that-be are in a certain sense permanent (cf. the life work of Antonio Negri, in particular

this,

this,

this and

this). There is a positive/progressive accumulation of the gains made in struggle that parallels the (negative, repressive) accumulations of capital and power. This is not a contradiction of the principle that there can always be a reversal to oppression and a loss of spirit after a progressive victory. Because of the positive accumulation of struggles, the political and capitalist powers-that-be are forced to innovate in their techniques of control

and exploitation. This very thing is happening in Ukraine right now, and most of Yushchenko's oranges are reduced today to a scramble, not to stop this innovation, but to hold on to a meager share of the power they so quickly and unwittingly ceded to their oligarchic adversaries out of the blindness of their beliefs/interests and/or the hubris of their personalities.

T

Thus, after a victory of the oppressed, the powers-that-be can no longer rely solely on previous techniques, but there always-already are new techniques of control and exploitation to be invented and combined with older ones. Many critics have pointed out that two central limitations of Marx's thought were a) his failure to foresee the flexibility of capital and capitalist forms of rule in

overcoming economic and political crises and, relatedly, b) his conviction that crises would necessarily lead to capitalism's collapse. For all their talk about needing stability in the market, capitalist powers have over and again demonstrated they can strive in times of crises, for it is in the resolution of crises that they can reassert their power and control, often with greater

depth than before (cf. Negri, again). This process of reassertion is taking place in Ukraine right now, and Yushchenko and gang have enfeebled themselves to such an extent that they are not able to stop it (and it is likely that some among them benefit from and support the Kuchmism-lite system). Thus two similar criticisms of Yushchenko and gang

and their apologists can be made:

a) They overestimated their societal level of support and gravely underestimated (due to their ideology? or meak personalities? or their own vested interests?) and therefore failed to appreciate the flexibility of their oligarchic adversaries;

b) They foolishly believed that their oligarchic adversaries would eventually capitulate--because of reasoned orange arguments and proclamations without any real orange stick--to full

cooperation with an orange power, and become a kind of consolidated-on-orange-terms "national bourgeoisie." This latter bit was more an element of faith--not of some kind of level-headed pragmatism--that entered into their beliefs, willy-nilly. And so once again, religious leaders have failed to deliver to Ukrainians that for which they so long have prayed.

T

Thus, though positive change has happened in Ukraine--the minimum that was possible after the Orange Revolution--one should not prematurely think the struggle is over, nor that the Spirit of the Orange Revolution will live on without ongoing efforts. Ukraine after the Orange Revolution is stuck in a semi-realized state and is stuck with a

plethora of top-level politicians who leave much to be desired (

including Tymoshenko). This situation requires that the people who dreamed of much more and who felt the spirit two years ago renew their efforts in building a real movement for change in their country. I fear that no political force in Ukraine today is capable of delivering what the multitude of Ukrainians dreamed of or glimpsed in Nov-Dec. 2004. That force is still waiting to be made.

Thus the most basic but important work of organizing and solidifying a real grassroots movement against corruption and elite intrigue is still of the upmost importance in Ukraine--and this is the reason why the ruination of Pora! as the embryo of a real, all-Ukrainian grassroots movement by the hubris of one man and the pretension of becoming a political party was one of the greatest tragedies of the post-OR days. But it is not a tragedy that can not be overcome.

S

Spirit is nothing without struggle; spirit will perish if concrete struggle does not continue.

F

For this reason, those who continue to occupy tent camps and to protest in Kyiv and across Ukraine, and who picketed outside of Yushchenko's elite gathering for the OR's anniversary, and who otherwise refuse to make any apologies for the way in which Yushchenko and team have betrayed "the people of the maidan," are in my opinion doing the right thing.

Of course, in the end, one should give credit where credit is due: the press is a degree freer, elections cleaner, civic activism a degree higher, and some moderate success has been gained in Ukraine's culture wars (Yushchenko's success on one front of the culture war--i.e., recognition of the

holodomyr as genocide--is respectable). And the oligarchy-elite remain as firmly entrenched and in power as ever.

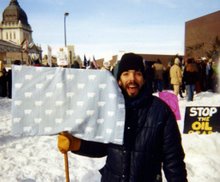

*All but the last five fotos, which were taken in Kyiv, are still-fotos captured from digital video that I took in various locations in Western Ukraine during the OR.

Spirit is nothing without struggle; spirit will perish if concrete struggle does not continue.

Spirit is nothing without struggle; spirit will perish if concrete struggle does not continue. For this reason, those who continue to occupy tent camps and to protest in Kyiv and across Ukraine, and who picketed outside of Yushchenko's elite gathering for the OR's anniversary, and who otherwise refuse to make any apologies for the way in which Yushchenko and team have betrayed "the people of the maidan," are in my opinion doing the right thing.

For this reason, those who continue to occupy tent camps and to protest in Kyiv and across Ukraine, and who picketed outside of Yushchenko's elite gathering for the OR's anniversary, and who otherwise refuse to make any apologies for the way in which Yushchenko and team have betrayed "the people of the maidan," are in my opinion doing the right thing. *All but the last five fotos, which were taken in Kyiv, are still-fotos captured from digital video that I took in various locations in Western Ukraine during the OR.

*All but the last five fotos, which were taken in Kyiv, are still-fotos captured from digital video that I took in various locations in Western Ukraine during the OR.