That is, Baba Omaha says that during her childhood in Chetverylivka everyone said “spasybi” and “velyki spasybi,” and that the first time she heard “djakuju” being commonly used was from Galicians in the DP camps after the war. She also says that the first time she heard Russian was when Bolshevik soldiers came to her family’s home, labeled them kulaks and took away their tractor (which was one of two used by everyone in the hutor, while her father did the maintenance on both the tractors), animals, and foodstuffs, including all the bread and grain they could find. She began to learn Russian after surviving the holodomyr in a new school that was established on the new collective farm. She recalls having her teacher put a bar of soap in her mouth for refusing to speak. Baba Omaha is neither a particularly patriotic nor unpatriotic person; she is best described as deeply humanist. It seems that, as a young girl she was simply able to detect the inhumanity of linguicide. . .

It was in the DP camps that she came into touch with both sides of Galician nationalism, i.e., with both its divisive and polarizing aspect as well as its admirable and unifying aspects. The Galician patriots she met complained bitterly about her supposedly Russified speech. Baba Omaha insists that she never learned Russian very well, though she has a better than average facility in languages, especially in other Slavic languages.

In order to survive socially in the camps, Baba Omaha says she quickly learned to speak proper Galician dialect. Before then, she had learned Polish well enough to fake it in the Polish side of the DP camps until the allies stopped sending former Soviet citizens back to murder and exile; she therefore learned to get by in Polish before she settled among the remaining Ukrainians in the camps. From Poltava, she had never heard Polish before then and says that she spoke very little, only what was necessary, so as not to give herself away--which she of course eventually did, but that’s another story. Still before then she had learned quite a bit of German during her time as a Nazi slave, and she often tells the story of an encounter with a German officer in such vivid detail, using such fluent German phrases, that she practically becomes that officer in the acting-out of the role he still plays in her memory. Her second husband was a Czech fellow who, like she, was a post-war refugee to the West and whose tongue she learned quite well. She also had a Belarusyn friend in Omaha who spoke actual Belarusyn, from whom she learned quite a bit. That she had learned to speak Galician-dialect Ukrainian in the camps also helped socially when she settled in Omaha. Omaha’s Ukrainian community was a feature of the post-war immigration and has been, like many other Ukrainian communities of North America, Galician-dominated.

However, her native dialect has lurked in her subconscious, and as she gets older and the tasks of self-conscious control become more difficult, some of her native Poltavan manners of speaking reappear. Thus, she has this story to tell: A few years back, she hitched a ride home after an event at the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church of Omaha from one of the more prominent members of that community, a Galician woman. Baba Omaha has never learned to drive, and so getting out of the woman’s car she said, “Nu, Pani, velyki spasybi.” This Pani replied by saying something like, “Oh, Halja, after all these years, you still don’t speak proper Ukrainian” Then to paraphrase what Baba Omaha next said to me (and pardon the fact that I did not type this out in Ukrainian Cyrillic, and that I left out soft signs, and that I probably made other mistakes, especially with grammatical marks; my Ukrainian, my first language as a child and then later lost, is now a second language mostly reconstructed from listening and a little studying. . .):

“Jaki ukrajintsi vony domajujut Vony je? Ja mozhu skazaty shcho Vony, Halychany, rozmovljajut majzhe jak Poljaky! Ja nikoly ne chula rusku movu, tilkyj koly Bilshovyky pryjikhaly do nas v hutori i skazaly shcho my kuljaky, i vzjaly vsjo. . .vsjo. . .vid nas. Todi mala ja vchyty rusku movu v shkoli, v novymu kolkhospi, ale ja pohano vchyla. Po pershe meni ne spadovalasja vchyty, bula ja taka pohana studentka. A takozh ja bula taka uperta. . .Pomjataju shcho ja, kolys, mala sisty z mylom u buzi bo ja ne khtila hovoryty po jikhnomu, po ruski. Ja bula dytyna, i pomjataju shcho ja vidchuvala shcho, to ne je moja mova. A my vzhe skazaly spasybi v hutori. Tse takozh ukrajinska mova. Akh, Stefane, ty znajesh jak Ukrajintsi je! Vony tak ljubljut svarytysja, a khto je Ukrajinets, a khto ne je. . .A ja zavzhdy dumala shcho my vsi Ukrajintsi!”

*****************

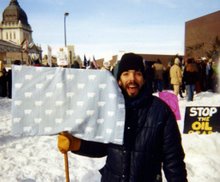

Who's the Smiley American? Me with my second-cousin Olja in Poltava

Who's the Smiley American? Me with my second-cousin Olja in Poltava

Note: perhaps spasybi is a Ukrainianized version of a Russian word. I don't know, and although I am not a linguist (though linguistics fascinates me), it does seem that perhaps both spasiba and spasybi derive from an old East Slavic root. I beg more knowledgeable people to comment here. But the overall gist of how Baba Omaha has been treated at times by fellow emigre Ukrainians conveyed here is quite accurate.

Update 2: Just for the sake of balance, I hope that readers will recall that I have strong roots in Galicia and spent nearly a year during the past two years residing and participating in the life of the town of Pidhajtsi, a town in the heart of Halychyna. For example, see this; this, especially the comments section; and more or less all of the posts during the month of November and October, which contain posts with photos of life and work in Pidhajtsi, or in a town in the heart of Galicia/Halychyna. I am proud of my Galician heritage!

Update 2: Galician nationalism was the rock upon which the tidal wave of Little Russianism that was rolling across Ruthenia once and for all broke before striking land. The waters of that tidal wave are still receding and continued storms in the north and east slow the process; our great hope of course is that there is not another major earthquake in the north that pushes yet another massive wave of Little Russianism across the land. (Perhaps some else has come up with this metaphor elsewhere. . .)

5 comments:

You are a very good story teller my friend. I really like reading your blog. Thank you for a fresh breath of air. Real stories about real people.

Once again, thanx a million for the compliment. I indeed enjoy writing these pieces most of all. . .pieces that are focused on a real life story that, in the course of the telling, have a lot to say about history and politics. . .

What you write about in terms of people encountering Galician nationalism in dp camps and how divisive it was, is true. Even to determining who got what quality of food. I heard stories from my mom who lived in a dp camp, whose family is from eastern Ukraine. And she, like Baba Omaha, states that people from Galicia speak with a Polish accent, which they call "Ukrainian". And I believe that although the Galician nationalism can be a positive it also has its deficits which are rarely acknowledged or discussed.

Thanx for the comment, anonymous, and sorry for the delay in response. I am curious to learn what part of Ukraine your family is from. I was talking the other day with a woman at our local Ukrainian Credit Union in Minneapolis who told me that she too learned to speak Galician dialect when she married a Galician, while her own family was from the Kyiv region. She and her husband were born in the camps and raised in the US, so they are first-generation Ukrainian-Americans.

I don't want my comments to be at all taken as anti-Galician; one might say that without Galician-Ukrainian nationalism, Little Russianism probably would have conquered our ancestral homeland to the extent that it has in Belarus'. But I do believe that the negative aspects of a bit-too-extreme pride need to be pointed out.

This is especially the case when Ukrainians become themselves chauvanist, either by arguing who the real Ukrainians are, or by insisting that certain other groups are Ukrainian. (I.e., I am refering to the ongoing matter of Rusyn national identity; if you don't know what I am talking about, that's alright--I have been working on a piece on the Carpatho-Rusyns that I hope to post here sometimes in the near future, where you can find out what the issue is. . .)

It is not only arguing who the real Ukrainians are but also what is the real Ukrainian language and culture. It boggles my mind that Ukrainians sub-divide themselves, as if we did not have enough outside people willing to do it for us? Regional backgrounds become the "us" and "them" and this is important as it influences the direction/s and focus which organizations take - (aside from prejudices). Namely, I am referring to human trafficking, prostitution, drug use, orphans, runaways and HIV infection. How many diaspora org. are involved with those target at risk populations? Ukraine has the highes rate of new HIV infections but you would not know it if you were involved in diaspora org.

Post a Comment